Beyond Jefferson: Changes to Virginia’s State Capitol

The Clérisseau drawings and the Fouquet model reached Richmond separately in 1786. The existing construction on the Capitol site was adapted to Jefferson's conception, but Jefferson's designed was adapted, too, during the long period of construction from 1786 to 1798.

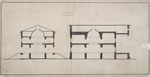

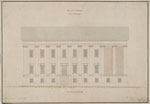

It was probably a Richmond builder named Samuel Dobie (d. 1801) who extensively altered Jefferson's design. The low podium that Jefferson intended was replaced by a full basement to hold the offices, which Jefferson had impractically put high on the third floor. The Richmond builders executed a colossal single portico two columns deep and wrapped this Ionic Order around the entire exterior in the form of pilasters. The front steps were eliminated so the basement offices along the south front could have windows. The Ionic Order now had a kind of capital popularized by Palladio's successor Vincenzo Scamozzi (1548-1616). Jefferson wrote that he had "yielded, with reluctance," to Clérisseau's preference for this capital. Clérisseau's sunken panels were included minus their garlands. The top story was a garret with no windows in the outer walls and briefly had some kind of "flat" roof. Jefferson's idea for a Conference Room, with forty columns and no dome, gave way to a room with a dome, no columns, and a gallery boldly supported on brackets. Most of the detail inside and out was altered into un-Jeffersonian patterns.

Thomas Jefferson's dismay at the changes in the design of the State Capitol was understandable. His design was altered to fit an already-begun foundation, its embellishments were altered, it was placed on a high basement, and the portico was shorn of its steps. Nonetheless, the practical layout and the grandeur of the conception survived. Jefferson himself wrote in 1789 that "our new Capitol … whenever it shall be finished … will be worthy of being exhibited along side the most celebrated remains of antiquity." The Capitol was completed in 1798 and throughout the 19th century, maintenance cycles of attention and neglect, almost always driven by the availability of state funds, forced the structure to change.

Albert Lybrock.

Digital reproduction of carte de visite.

ca. 1860. Private collection.

Albert Lybrock (1827-1886) was trained in Germany and came to the United States in 1849. He was first employed in New York City before moving to Richmond. He became one of the leading professional architects in the city and is best remembered for designing both the cast-iron canopy over the grave of James Monroe in Hollywood Cemetery and the U.S. Customs House.

In 1857 a joint committee of the Virginia General Assembly was formed to receive proposals to enlarge the facilities of the Capitol building, and Lybrock was paid $100 for submitting drawings. He proposed adding a bay to the rear of the Capitol, expanding the space available for the General Assembly, and rearranging some of the interior spaces. Lybrock's most dramatic change was to remove the side entrances and build the front steps that were intended by Jefferson and modeled by Fouquet. The Civil War interrupted the project, and Lybrock's proposals were never put in place.

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

For historians, Lybrock's drawings are important not for what the architect proposed, but for what he recorded on these sheets. Lybrock made measured drawings of the Capitol building as it stood in 1858. These drawings represent the most-complete documentation of the Virginia Capitol before the sweeping changes to the building that took place between 1904 and 1906. During these later modifications, front steps, similar to those Lybrock had suggested almost fifty years earlier, were built, giving the Capitol the distinctive appearance of today.

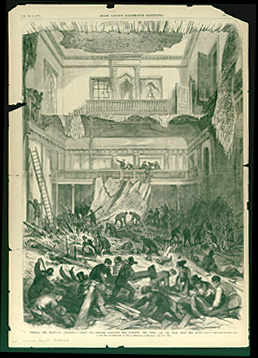

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, plans for the Capitol's improvement ceased. The Capitol housed both the Virginia General Assembly and the Confederate Congress. Photographs of the Capitol at the end of the war depict a building badly in need of repair.

William Ludwell Sheppard (1833-1912). Published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 14, 1870. Digital reproduction of wood engraving.

Library of Virginia.

The worsening condition of the Capitol became tragically apparent when the balcony of the third-floor courtroom collapsed in April 1870 during arguments before the Supreme Court of Appeals about a hotly disputed Richmond mayoral election. The floor of the courtroom crashed down into the chamber of the House of Delegates one floor below. More than 60 persons died in what came to be known as the "Capitol Disaster." Despite some calls to raze and replace the damaged Capitol, the legislators approved funds and repaired the building.

The Capitol remained overcrowded and poorly maintained until the General Assembly decided in 1901 to enlarge and modernize the building. Sponsoring a design competition, the General Assembly rejected proposals that would significantly alter the exterior appearance of Jefferson's conception. The design finally chosen acknowledged the primacy of Jefferson's "temple on the hill" by creating new, separate assembly halls for the Senate and the House of Delegates, each flanking Jefferson's Capitol and attached to the Capitol by hyphens. Early in the 1960s the hyphens were widened, yet the original section of the Capitol remains the dominant architectural feature in the composition.

Capitol Square Preservation Council Collection.

Courtesy of the Library of Virginia