Select a constitution to view by clicking one of the links below.

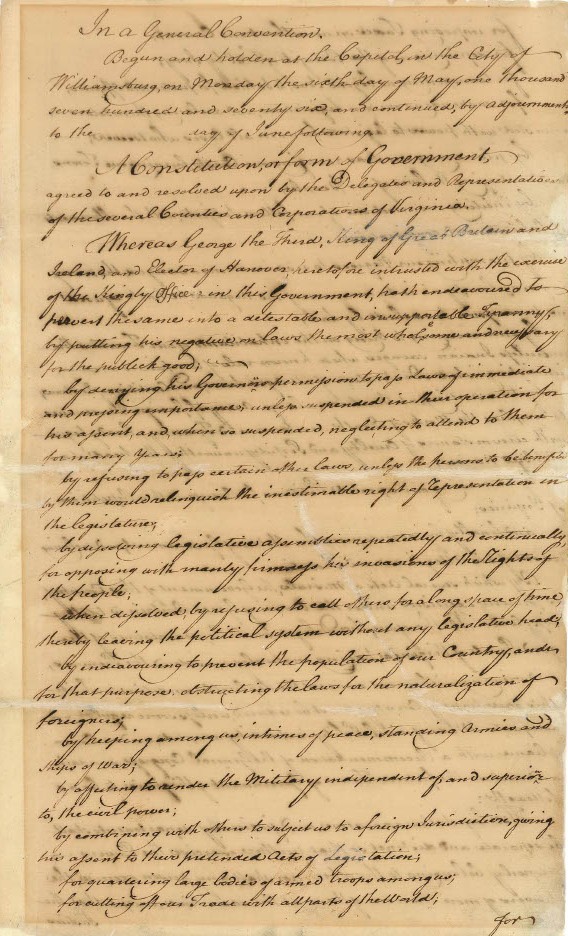

1776 Constitution

The Convention of 1776 met in the Capitol in Williamsburg from May 6 through July 5, 1776. On 15 May the elected delegates unanimously instructed Virginia’s representatives in the Continental Congress to introduce a resolution of independence; on June 12 they unanimously adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights; and on June 29 they unanimously adopted the state’s first “Constitution or Form of Government.” The declaration was the first of its kind in the new United States and as such might have been even more important in several respects than the state constitution, which was the first that was not intended as a temporary bridge between colonial and independent status.

The Constitution of 1776 continued without change the colonial practice of allotting each county, regardless of size or population, two members in the House of Delegates, and it created the new twenty-four-member Senate of Virginia. It authorized the General Assembly to elect the governor annually as well as judges of courts of admiralty, common law, equity, and appeal. It deliberately made the executive weak and dependent on the assembly and prohibited the governor from acting without the advice of a twelve-member Council of State that the assembly also elected. Suffrage remained as it had been under an act of 1736, limited to adult white men who owned or had a long-term lease on at least one hundred acres of land (or fifty acres and a house) in the country or who owned a lot or a part of a lot in Williamsburg or Norfolk. Under an ordinance that the convention adopted, all the laws then in force and not inconsistent with the new constitution remained in force, which allowed slavery to exist under authority of colonial statutes and also allowed unelected justices of the peace who served on the county courts to continue to function as before, including levying local taxes. It silently enabled parishes of the Church of England to continue to exercise their ecclesiastical and civic responsibilities (poor relief, etc.) as part of the government, the same as before. The January 1786 Act for Establishing Religious Freedom in Virginia effectively disestablished the church, and it ceased to be part of the government; another law of that year transferred poor relief from the church to new overseers of the poor in the counties. The Act for Establishing Religious Freedom and the Declaration of Rights were separate documents from the Constitution or Form of Government, but both had constitutional status. The convention ordained the constitution in effect without a ratification referendum.

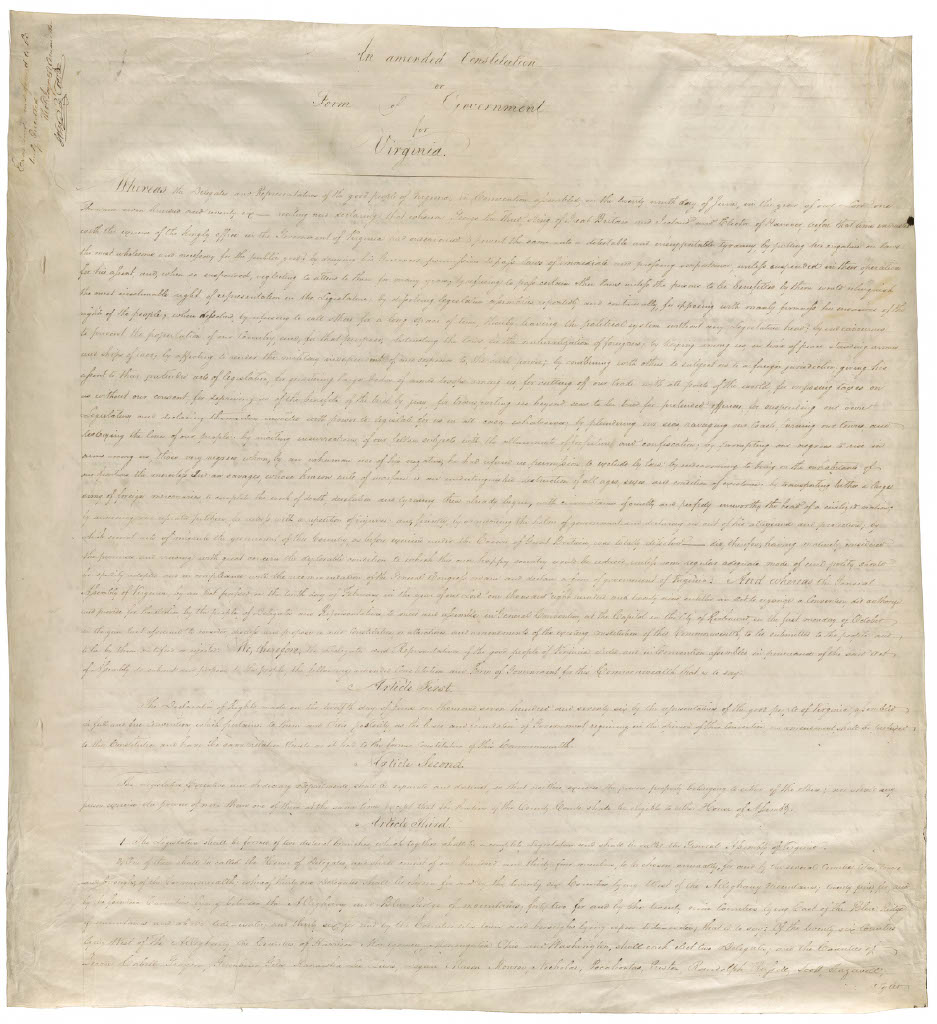

1830 Constitution

The Convention of 1829–1830 met in the Capitol in Richmond (or for a time in nearby First Baptist Church while the General Assembly was in session) from October 5, 1829, through January 15, 1830. On January 14, 1830 the elected delegates approved a new constitution by a vote of 55 to 44. Voters ratified it in a referendum in April 1830 by a vote of 26,055 to 15,536. The new constitution reapportioned the state to guarantee that voters east of the Blue Ridge would always be able to elect majorities in both houses of the General Assembly (to protect the interests of slave owners, who were more numerous in that region than elsewhere), even though population data available to the convention indicated that within a decade a majority of white males would reside west of the Blue Ridge. The constitution left the executive a weak office, but it reduced the number of members of the Council of State from twelve to three and changed the governor’s term of office from one year to three years without eligibility for reelection. The General Assembly retained the authority to elect all the state’s judges except justices of the peace. The constitution relaxed the property qualification for the suffrage and allowed adult white men who paid taxes to vote, which enlarged the electorate moderately.

The new constitution did not mention institutions of local government, which left the undemocratic county courts able to continue operating as they had since the 1620s and left municipal governments to operate as they had under their individual charters, which the General Assembly had enacted as state laws. It also included the essence of the 1786 Act for Establishing Religious Freedom in the body of the constitution. Except in some matters of detail, the Constitution of 1830 did not significantly alter the manner in which government and politics functioned in Virginia from the manner in which they had functioned under the Constitution of 1776.

1851 Constitution

The Convention of 1850–1851 met in the Capitol in Richmond in two sessions, from October 14 to November 4, 1850 and from January 6 to August 1, 1851. The elected delegates approved the new constitution by a vote of 75 to 33 on July 31, 1851, and voters ratified it by an overwhelming vote of 75,748 to 11,863 on October 23, 1851. The Constitution of 1851 made several important sharp breaks with the past. It allowed universal, white manhood suffrage for the first time and also for the first time permitted voters to elect most public officials, including the governor, lieutenant governor (a new office), and attorney general for four-year terms, all the state’s circuit and appellate court judges, and justices of the county courts as well as several other local officials. The new constitution reduced the frequency of legislative sessions from annual to biennial and limited the duration of sessions, as well. The Constitution of 1851 established a system of circuit and appellate courts that imposed a larger measure of uniformity in the state. It also explicitly protected slavery with several new provisions. It revised the apportionment scheme of 1830 to allow voters west of the Blue Ridge to elect a small majority of members of the House of Delegates but guaranteed that a majority of members of the Senate of Virginia be elected from the eastern region of the state where slavery was most important; it prohibited public and private manumissions; and it limited the amount of taxes that the assembly could impose on slave property.

The Constitution of 1851 remained in effect in the portion of Virginia that became one of the Confederate States of America until government officials abandoned Richmond early in April 1865 and thereafter left it unenforced; it also remained in effect in the loyal/liberated/occupied parts of Virginia that became West Virginia in 1863 and until April 1864 in the loyal/liberated/occupied counties and cities of eastern Virginia that remained one of the United States of America during the Civil War. That government was called the Restored Government because it was the government of the state that men loyal to the United States restored to the Union in June 1861.

1864 Constitution

The Convention of 1864 met in the United States Courthouse in Alexandria from February 13 through April 11, 1864. Voters elected seventeen convention members from the loyal/liberated/occupied counties of Loudoun and Fairfax and the city of Alexandria in northern Virginia, the counties of Northampton and Accomack on the Eastern Shore, and the counties of Warwick, Princess Anne, Norfolk, New Kent, James City, Elizabeth City, and Charles City and from Williamsburg, Portsmouth, and Norfolk, all in southeastern Virginia. The members of the convention adopted the new constitution by a vote of 13 to 4 on April 7, 1864 and after a debate for which no records survive voted to proclaim it in effect without a ratification referendum as of the date of the convention’s adjournment.

The new constitution made few changes to the basic features of the Constitution of 1851, but it included a small number of very important changes. It required for the first time that voting be by ballot rather than by public voice vote. It disfranchised most Virginians who supported the Confederacy unless they renounced their actions. It omitted the apportionment scheme that had enabled voters in the portion of Virginia where slavery was most important to elect a majority of members of the Senate of Virginia. And it abolished and prohibited slavery in Virginia forever. Unfortunately, we as yet have no good scholarship to indicate what, if anything, officials of the Restored Government or in its counties and cities did to enforce that provision during the year between the end of the convention and the end of the war. In spite of some defective scholarship early in the twentieth century that indicated that the Constitution of 1864 was of doubtful legitimacy (scholarship which has misled nearly all of us until quite recently), government functioned under the Constitution of 1864 in all of what remained Virginia until the Constitution of 1869 superseded it.

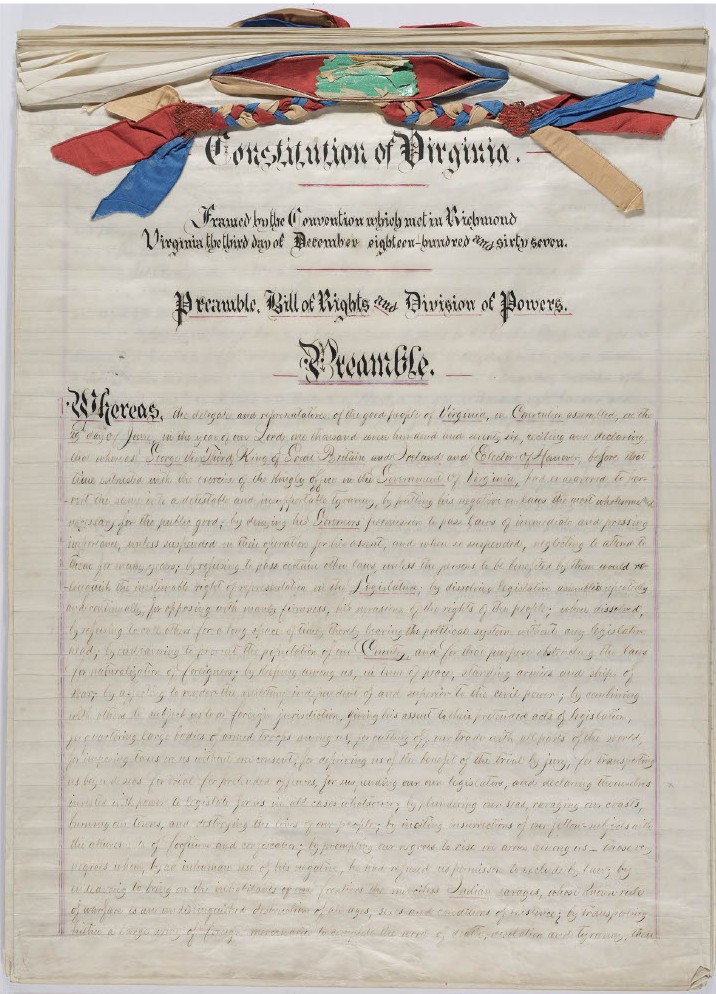

1868 Constitution

The Convention of 1867–1868 met in the Capitol in Richmond from December 3,1867, through April 17, 1868. Voters elected the members on October 22, 1867, under authority of an act of Congress of March 3, 1867, that required most of the states of the former Confederacy to write new constitutions before it would admit their senators and representatives to their seats in Congress. The delegates were the most diverse by occupation, background, class, and race of any Virginia convention before or since. Twenty-four African American men won election to the convention in the first election in Virginia’s history in which Black men voted. Delegates adopted the new constitution by a vote of 51 to 26 on April 17, 1868, but the ratification referendum did not take placed until July 6, 1869, when voters ratified it by an overwhelming vote of 210,585 to 9,136 and stripped out of it two clauses that disfranchised supporters of the former Confederacy and barred them from public office.

In several important respects, the Constitution of 1869 was an even more far-reaching democratic reform document than the Constitution of 1851 had been. The new constitution enfranchised African American men. It required the General Assembly to create a statewide system of free public schools for all children. It guaranteed voting by ballot. In the first article on local government in any Virginia constitution it created the board of supervisors form of county government and authorized the popular election of a larger number of local officials than at any previous time. It inserted the Declaration of Rights (renamed Bill of Rights) into the constitution for the first time as Article I. Two new sections of the Bill of Rights in effect renounced the right of secession and proclaimed the Constitution of the United States and the laws and treaties enacted under its authority the supreme law of the land, which renounced the doctrine of states’ rights that Southern politicians had relied on to protect slavery. Another proclaimed “That neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as lawful imprisonment may constitute such, shall exist within this State.” And another “That all citizens of the State are hereby declared to possess equal civil and political rights and public privileges.” And yet another declared “That rights enumerated in this bill of Rights shall not be construed to limit other rights of the people not herein expressed. The declaration of the political rights and privileges of the inhabitants of this State is hereby declared to be a part of the Constitution of this Commonwealth, and shall not be violated on any pretence whatsoever.” The Constitution of 1869 was also the first to provide a method of amendment.

1902 Constitution

The Convention of 1901–1902 met in the Capitol in Richmond from June 12, 1901, through June 26, 1902 (except for a few weeks when it met in the nearby Mechanics’ Institute while the General Assembly was in session). The one hundred white, male elected delegates included more than a dozen Confederate veterans and an even larger number of sons, grandsons, and nephews of Confederates and also twenty-two judges or former judges and one future chief justice of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. On May 29 they voted 47 to 38 with six sets of pairs to ordain the new constitution without a referendum. The purpose of the convention was to disenfranchise African American voters, which it achieved by imposing a poll tax and complicated registration regulations that allowed registrars to deny registration to just about any man they did not want to vote. To achieve the objective, the complex and detailed disfranchisement article was almost as long as the entire Constitution of 1776 had been. Throughout the new constitution, detail abounded, as in most other state constitutions of the time, detail that was more statutory in character than constitutional. The article on education explicitly forbade the education of “white” and “colored” students in the same schools. The new constitution included a new article on municipal government (the first) that implicitly recognized the state’s unique system of independent cities. It also created a fourth branch of state government, the State Corporation Commission, which was one of the most innovative and effective state regulatory agencies in the United States.

1928 Constitution

Voters ratified a revised version of the Constitution of 1902 by a vote of 74,109 to 60,531 on June 19, 1928. The General Assembly submitted the revision to the voters in the form known in parliamentary practice as an amendment in the form of a substitute to revise many of the articles in the Constitution of 1902 but without fundamentally altering the structure or most of the main provisions of the old constitution. Governor Harry Flood Byrd proposed the revision in 1926 as part of a plan to streamline state government and make it more efficient in order to reduce taxes. He hired a consulting firm to study the operations of executive agencies, an analysis that a select committee of lawyers and judges that he also appointed used as a blueprint to draft a proposed revised constitution for the General Assembly to consider and amend at a special session in 1927. The governor also appointed a rubber-stamp citizens’ advisory committee that unsurprisingly endorsed all the governor’s proposals, which included reducing the number of statewide elected officials from seven to three and prohibiting the state from taxing real or personal property to leave that source of revenue exclusively reserved to cities and counties. The governor’s consultant also studied the operations of county governments and made numerous far-reaching proposals for reform. The governor and citizens’ advisory committee refused to publish the consultant’s report on county government at the time, which killed it and prevented any changes being proposed to county government. What were called “courthouse rings” controlled government and politics in most counties in the interest of supporting the governor’s undemocratic, white supremacy faction of the state’s Democratic Party. The principal consequence of the constitutional revision was to strengthen the office of governor in management of the state bureaucracy; but because the governor was also the man in charge of the Democratic Party organization, it also strengthened the organization and enabled Byrd to command the most durable and long-lasting state political machine in the country’s history.

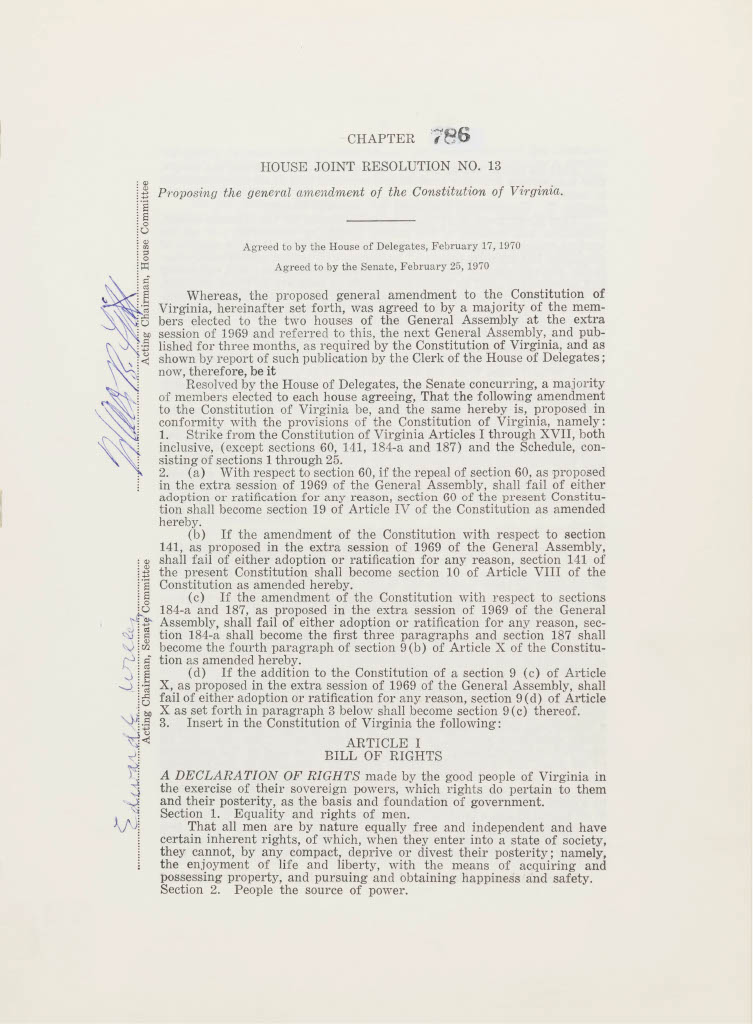

1971 Constitution

The Constitution of 1971 was also the result of a governor’s proposal to appoint a commission on constitutional revision to suggest changes that the General Assembly could consider before it submitted to the voters an amended new constitution in the form of a substitute for the old. Voters ratified the new constitution by a vote of 576,776 to 226,219 on November 3, 1970, and it went into effect on July 1, 1971. It omitted the poll tax and all the other barriers to voting, the requirement for racial segregation in public schools, and much of the statutory detail that had been in the previous constitutions. It also prohibited governmental discrimination based on “religious conviction, race, color, sex, or national origin” and in effect granted to every school-age person in the state a right to a high quality education in a public school. The new constitution also conformed to the “one person, one vote” requirements that federal courts imposed on the states in the 1960s and for the first time required that all electoral districts in the state contain approximately equal populations. It collapsed the two long articles on county and municipal governments in the 1902 and 1928 constitutions into a short, new article that in effect blurred the distinctions between them. A very important change that the constitution contained, and which had in large part convinced the governor of the necessity for constitutional revision, was to remove some of the barriers to issuing bonds that had prevented state and local governments from borrowing enough money to meet new demands of the state’s citizens. The new constitution also included an important new article on conservation that committed the state government to a policy of protecting the air, water, and natural resources of the state.

On January 8, 1969, Governor Mills Godwin; Albertis Harrison, former governor of Virginia and chair of the Commission on Constitutional Revision; and A.E. Dick Howard, executive director of the Commission, offered remarks to the press ahead of the official release of the Commission's report on January 11, 1969. Listen to the Press Release