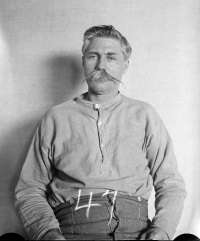

Floyd Allen (5 July 1856–28 March 1913), principal in the 1912 gunfight in the Carroll County Courthouse, was the fourth of seven sons and fifth of eleven children of Jeremiah Allen and Nancy Combs Allen. He was born in Carroll County, where members of his father's family had lived as farmers, stockmen, and distillers for decades prior to the county's formation in 1842. Jacksonian Democrats in politics before the Civil War and Primitive Baptists in religion, the Allens at the time of Floyd Allen's birth shared in the nonslaveholding, egalitarian culture of their time and locale. His father and eldest brother served in the Confederate army, and the family experienced the deprivations common to the Civil War period.

After Appomattox the family improved its economic and social standing. Jeremiah Allen served for a time as a township supervisor, and his sons flourished as farmers, lumbermen, gristmill operators, distillers, storekeepers, real-estate speculators, and part-time preachers and teachers. One of the boys, Sidna, even ventured north to the Klondike in 1898 in an unsuccessful quest for gold. Enterprising and hardworking, several family members became what mountaineers called "high livers," residing in modern houses with telephones and other conveniences, owning and riding fine horses, and educating their sons for business or professional careers.

Floyd Allen was one of those who aspired to the high life. Although he had almost no formal schooling, he accumulated an estate worth between $10,000 and $20,000 by farming, keeping a store, and dealing in real estate. An ardent Democrat, he was elected or appointed to stints as deputy sheriff, constable, and county supervisor. On 9 August 1877 he married Cornelia Frances Edwards, of Carroll County, who was described in contemporary sources as a devoutly religious woman and a gracious hostess. Of their three children, one boy died in childhood. The elder surviving son, Victor Allen, seems to have enjoyed few advantages and became a rural mail carrier. Floyd Allen Jr. later changed his name to Claude Swanson Allen, after a Pittsylvania County Democrat who served successively as congressman and governor. Thanks to his father's increasing wealth, the younger Allen attended a private boarding school near Hillsville and enrolled for a time at a business college in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Although contemporary accounts characterize Floyd Allen as well-dressed, courteous in his routine business and personal contacts, and better informed about current events than most of his neighbors, his personality also had a darker, more ominous aspect, with a propensity for violent rage arising from an uncontrollable temper. According to family sources he was so unmanageable during his youth that his mother sometimes restrained him with ropes. As an adult he occasionally came to blows with other Carroll County residents over politics, clashed with federal revenue agents about insults they had allegedly made while visiting his home, was fined for shooting a neighbor in the leg during a 1904 land dispute, and even engaged in a pistol duel with his equally pugnacious brother Jasper "Jack" Allen, in a confrontation that left both men badly wounded. Rumors also circulated that Floyd Allen had killed a black man for hunting on his property, an accusation that Allen vehemently denied.

Although they persistently denied any wrongdoing, Allen and several of his brothers probably combined their hot tempers with a willingness to stray occasionally beyond the strict confines of the law. Jack Allen and Floyd Allen were widely reputed to have sold moonshine liquor, and in 1910 federal authorities in North Carolina charged Sidna Allen with counterfeiting. He was acquitted but subsequently indicted for perjury

Family proclivities for personal violence exposed the Allens to the attentions and arrest warrants of hostile law-enforcement officers. Political trends in Carroll County eventually augmented this vulnerability, setting the stage for the disaster that was to come. Led by Dexter Goad, a strikingly adept and somewhat unscrupulous organizer, the county's Republicans captured the major local offices between 1904 and 1911, installing William M. Foster as commonwealth's attorney, Lewis F. Webb as sheriff, and Goad himself as clerk of court. Firm in their traditional Democratic allegiance, Floyd Allen and most of his relatives opposed these Republican inroads, but Jack Allen temporarily collaborated with the new courthouse incumbents, allegedly because of promises that his illicit liquor business would receive official toleration. When the Republicans refused to nominate one of his sons for commonwealth's attorney, however, Jack Allen rejoined his brothers in opposition to, and increasingly embittered isolation from, the dominant elements at the county seat of Hillsville. From the Allens' perspective, the increased surveillance of their activities by federal revenue agents and the United States Secret Service's abortive prosecution of Sidna Allen for counterfeiting were not accidental. Instead, in the view of the Allens, Republican spoilsmen in Carroll County were cooperating with a Republican-controlled federal bureaucracy in a politically motivated campaign to harass and intimidate them.

The chain of events leading to the courthouse shooting began in March 1911 when two of Floyd Allen's nephews, Wesley Edwards and Sidna Edwards, became embroiled in a fistfight with four neighborhood boys during worship services conducted by their uncle Garland Allen, a Primitive Baptist preacher. Authorities in Hillsville issued arrest warrants charging the pair with disturbing a religious gathering. On advice from Floyd Allen, the young men fled to Mount Airy, North Carolina, in order to allow the situation to cool and to give Allen time to arrange for bail and to employ lawyers for their defense.

On 20 April 1911 Allen went to Hillsville, made the necessary arrangements, and agreed to bring his nephews to court for trial. As he was returning to his home in the southern part of the county, Allen met two deputy sheriffs who had already gone to Mount Airy and apprehended the fugitives without obtaining the necessary extradition papers. The officers were driving buggies and had the Edwards men in custody, their hands and feet secured with handcuffs and ropes. Enraged by what he regarded as a calculated insult to his family, Allen disarmed the deputies, assaulted one of them, released his nephews, and shortly thereafter turned them over to lawmen in Hillsville as he had earlier pledged to do.

The Edwards boys were convicted of the charges against them and served brief sentences in the county jail, but Floyd Allen's legal troubles had only begun. He was indicted for attacking the deputies and, after various delays, brought to trial in the March 1912 term of the circuit court. In the year that had passed between the incident and the trial, Circuit Court Judge Thornton Lemmon Massie, the lone Democrat in the law-enforcement bureaucracy at Hillsville, signaled his own good opinion of Allen by appointing him to a special police force.

The case was heard on 13 March 1912. The jury's verdict, however, was delayed until the next morning, when the little courtroom was packed with more than a hundred people, an astonishing number of whom were armed with revolvers or automatic pistols. Among those thus equipped were the defendant himself, his brother Sidna Allen, his son Claude Allen, his nephews Wesley Edwards and Sidna Edwards, and Jack Allen's son Friel Allen. Victor Allen was also in attendance, although apparently without a gun. Anticipating trouble, a large contingent of the county's Republican officials (the sheriff, four deputies, the commonwealth's attorney, the clerk of court, and the deputy clerk) were all armed as well.

The 14 March court session began in a routine way, with the consideration of various procedural matters. The jury then reported that it found Floyd Allen guilty and recommended a one-year term in the state penitentiary. His lawyers immediately requested that the verdict be overturned. Judge Massie rejected the appeal, but he agreed to conduct a hearing the next day at which additional witnesses would be interviewed and a final decision rendered on the motion for a new trial. Refusing a further plea that Allen be permitted to remain at large on bond until that time, Massie instructed the sheriff to take charge of the prisoner and escort him to jail. Sheriff Webb and Clerk Goad apparently made no secret of their satisfaction at the course of events, and Allen's notorious temper erupted. Declaring, "Gentlemen, I ain't a-goin'!" (or words to that effect), he began to search inside his coat and sweater for what he subsequently testified were subpoenas and what others claimed was a pistol.

What happened next has been the subject of endless debate. According to the Allens, several court officers opened fire on Floyd Allen, but other witnesses maintained that his son Claude Allen started the shooting, supported almost instantly by his uncle Sidna Allen. The consequences were horrible. The combatants exchanged approximately sixty shots in the crowded courtroom and more on the steps and in the yard outside. Killed immediately or mortally wounded were Judge Massie, Sheriff Webb, Commonwealth's Attorney Foster, juror Augustus C. Fowler, and a young spectator, Bettie Ayers. Clerk Goad was wounded in the face and a bullet fractured Floyd Allen's leg, while Sidna Allen suffered comparatively minor wounds.

Regardless of who started the battle, the Allens and their Edwards allies won it. Most of their surviving opponents fled the scene. It was then the Allens' turn to flee Hillsville, with the exception of Floyd Allen, who was too seriously injured to make the attempt, and Victor Allen, who remained to care for his father. The rest of the men took refuge in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Militiamen, bloodhounds, and posses organized and directed by the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency of Roanoke scoured the hills for them. Governor William Hodges Mann offered rewards for the capture of the fugitives, dead or alive, and threatened to prosecute anyone who aided their escape.

Discovered in a Hillsville hotel on 15 March 1912, Floyd Allen and Victor Allen were the first to be taken into custody. They offered no resistance, although Floyd Allen tried unsuccessfully to cut his own throat with a penknife. Various friends of the Allens who had been present in the courtroom were also temporarily placed under arrest. Between 22 and 29 March the pursuit turned up three more men: Claude Allen, Sidna Edwards, and Friel Allen, the last two of whom, according to some accounts, surrendered voluntarily. Sidna Allen and Wesley Edwards proved more difficult to capture. After eluding the dogs and posses for several weeks, they left the Blue Ridge on foot and then escaped by train from Asheville, North Carolina. Six months later Baldwin-Felts agents finally apprehended them in Des Moines on 14 September 1912.

Meanwhile, the commonwealth had begun to prosecute Floyd Allen and his kinsmen for the courthouse killings. The trials took place at Wytheville from April until December 1912. Juries empaneled for the successive cases from Virginia's southwestern and northern counties heard wildly inconsistent testimony. The prosecution made little or no effort to use ballistics tests or autopsy findings to demonstrate that a particular Allen or Edwards was individually and definitively responsible for any particular death. Instead, the state attempted to prove the existence of a premeditated conspiracy on the part of the defendants to murder the court officers, an approach that would make each of them equally liable for all of the deaths. Jurors generally resisted the tactic. On 16 May they convicted Floyd Allen of the first-degree murder of Commonwealth's Attorney Foster, but a prosecution of Claude Allen for the death of Judge Massie resulted in a jury finding of second-degree murder on the grounds that premeditation had not been proved. Claude Allen was then tried twice for murdering Foster, with one trial culminating in a hung jury and the second, after prolonged deliberations, ending with a first-degree verdict. In subsequent cases confessions to lesser offenses, plea bargains, and convictions for manslaughter or second-degree murder prevailed. Friel Allen and Sidna Edwards each received eighteen-year penitentiary terms, while Wesley Edwards was sentenced to twenty-seven and Sidna Allen to thirty-five years in prison. Victor Allen was the only defendant acquitted.

In September 1912 Judge Waller R. Staples, who presided at all of the trials, sentenced Claude Allen and Floyd Allen to die in Virginia's electric chair on 22 November. Governor Mann was unsympathetic to the Allens and a staunch advocate of capital punishment, but he nevertheless stayed the execution of both men on four occasions between November 1912 and March 1913 in order to permit them to exhaust their opportunities for appeal. Meanwhile, a dramatic shift of public opinion took place in their favor. Many people believed that the two men were no more deserving of the death penalty than their kinsmen who, in later trials, had received lesser sentences. Furthermore, defense attorneys in subsequent cases had shown that Dexter Goad and other officeholders were partially responsible for the courthouse tragedy. Reflecting these developments, petitions bearing tens of thousands of signatures urging executive clemency were submitted to the governor. Such prominent Virginians as Richard Evelyn Byrd, the Speaker of the House of Delegates; the Reverend George W. McDaniel, of Richmond's First Baptist Church; and U.S. Senator Claude A. Swanson exerted their influence to save the pair.

The Allens' public support became increasingly fervent, but their prospects for legal relief continually diminished. The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals twice rejected their appeals, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the convictions. Satisfied that further delay would be pointless, the governor reiterated his belief in the justice of the sentences and set 28 March 1913 as the execution date. On 27 March the campaign to save the two Allens took a final and particularly bizarre turn. With Governor Mann en route to New Jersey for a speaking engagement, lawyers for the condemned men approached Lieutenant Governor J. Taylor Ellyson with the suggestion that during the governor's absence from Virginia Ellyson had the right as acting chief executive to commute the death sentences. On the night of 27 March Ellyson asked Attorney General Samuel W. Williams to rule on the constitutionality of this proposal, and the penitentiary warden accordingly postponed the executions, originally scheduled for the next morning, until the legal question could be resolved. Informed of these intrigues by a late-night telephone call, Mann hastened back to Richmond by train early on 28 March and ordered that the executions be carried out.

At 1:30 P.M. on 28 March 1913 Floyd Allen was electrocuted in the penitentiary in Richmond. A few minutes later Claude Allen was put to death. Both men reportedly died bravely and without complaint. Over the protests of Victor Allen, the bodies of his father and brother were placed on public view at Bliley's Funeral Home in Richmond, where more than twelve thousand mourners and curiosity seekers viewed them. Transported back to Carroll County by train and wagon, Floyd Allen and Claude Allen were buried on 30 March 1913 in a cemetery near the Blue Ridge. A crowd estimated at five thousand persons attended the service.

Victor Allen and Cornelia Frances Allen eventually moved out of Virginia. Governor E. Lee Trinkle pardoned Sidna Edwards and Friel Allen in October 1922, and Governor Harry F. Byrd did the same for Sidna Allen and Wesley Edwards in April 1926. There were no pardons, of course, for those who died in the courtroom or for Claude Allen and Floyd Allen. Considered villains by some and martyrs by others, the Allens left their mark on the history and folklore of twentieth-century Virginia. Variously known as the "Hillsville Massacre" and the "Courthouse Tragedy," the violent episode left seven people shot dead or executed and four more serving long prison terms. It sparked controversies that simmered for generations. An array of newspaper accounts, magazine articles, and books have analyzed the much-disputed facts of the case, and mountain poets and balladeers have commemorated its tragic features, but many questions about the Hillsville gunfight and its participants remain unanswered.

Sources Consulted:

M. Clifford Harrison "Murder in the Courtroom," Virginia Cavalcade 17 (summer 1967): 43–47; Seth Williamson, "Hillsville Massacre," Roanoker 9 (Nov. 1982): 28–29, 44–51; Papers relevant to the Floyd Allen case, 1912–1922, Secretary of the Commonwealth Records, Record Group 13, Accession 21690, Library of Virginia; Elbert McNelie Colley Papers, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville; Etta Donnan Mann, Four Years in the Governor's Mansion of Virginia, 1910–1914 (1937); books reflecting an anti-Allen bias include Edgar James, The Allen Outlaws (1912), Edwin Chancellor Payne, The Hillsville Tragedy (1913), J. J. Reynolds, The Allen Gang (1912), and George M. N. Parker, The Mountain Massacre (1930); favorable books include J. Sidna Allen, Memoirs (1929), Elmer J. Cooley, The Inside Story of the World Famous Courtroom Tragedy [ca. 1961], and Rufus L. Gardner, The Courthouse Tragedy, Hillsville, Va. [ca. 1968]; also pertinent are Ethel Park Richardson and Sigmund Spaeth, eds., American Mountain Songs (1927), 34, Mellinger Edward Henry, ed., Folk-Songs From the Southern Highlands (1938), 317–320, and an account in verse by Samuel S. Hurt, "Gentlemen, I Ain't A-Goin" (1913).

Image in Records of the Virginia Penitentiary, Series II, Prisoner Records, Photographs and Negatives, Accession 41558, Library of Virginia.

Written for the Dictionary of Virginia Biography by James Tice Moore.

How to cite this page:

James Tice Moore, "Floyd Allen (1856–1913)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (1998– ), published 1998 (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Allen_Floyd, accessed [today's date]).

Return to the Dictionary of Virginia Biography Search page.