Westmoreland Delaware Davis (21 August 1859–2 September 1942), governor of Virginia, was born most likely in Paris, France, the location that both he and his mother stated several times late in the nineteenth century. Beginning in the second decade of the twentieth century, however, he let circulate a story that he had been born on a ship in the North Atlantic Ocean while his parents, Thomas Gordon Davis and Annie Harwood Lewis Morriss Davis, were returning from their annual summer holiday in Europe. Davis's father lived most of the time in Mississippi, where he managed five family plantations; his mother visited Mississippi only seldom and preferred to live at a Davis home in South Carolina. After his father and two older siblings died, probably from yellow fever, his mother took him to Virginia in 1860. They lived in the Richmond household of her paternal uncle, Richard Gregory Morriss, until he died in 1867. Davis's mother struggled for years to obtain an inheritance to which she believed she was entitled, but she was able to provide for Morley, as he was familiarly known, and sent him for a few years to an academy in Hanover County before he entered the Virginia Military Institute in 1873. Davis graduated near the bottom of his class in 1877 and attended the University of Virginia the following year. He may have taught school for two years before becoming a clerk for a railroad company in Richmond.

Davis attended law school at the University of Virginia during the 1884–1885 academic year and then moved to New York to study law at Columbia University, from which he graduated in 1886. He prospered during the next decade and a half practicing corporate law in New York. Davis joined exclusive clubs and became a well-known member of the foxhunting set. In London, England, on 7 August 1892 he married Marguerite Inman, a member of a wealthy Georgia family that owned part of a New York brokerage firm. They had no children.

In 1903 Davis had become wealthy enough to retire from the practice of law. He purchased Morven Park, a 1,200-acre estate with an elegant twenty-five-room mansion in Loudoun County, and moved to Virginia. He became a gentleman planter and prominent member of the riding and foxhunting society of Virginia and Maryland. At that time Davis stopped using his middle name or initial. He took a serious interest in scientific agriculture and turned Morven Park into a well-known livestock and dairy farm. He studied progressive farming practices in Wisconsin and helped establish the Virginia State Dairymen's Association in 1907. In January 1909 Davis became president of the Virginia State Farmers' Institute. He used the office to encourage farmers to organize as a political interest group and to lobby the General Assembly for increased appropriations for agricultural education, especially at Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College and Polytechnic Institute (later Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University). Davis published his ideas in the influential Southern Planter and also led a successful campaign to have the state construct two plants for grinding limestone for inexpensive sale to farmers with acidic soils. He purchased the Southern Planter early in 1912 and published it until his death. Davis acquired a controlling interest in the Warrenton Times in 1915 and in 1921 purchased the Leesburg Loudoun Times, which merged with another newspaper to become the Loudoun Times-Mirror in 1924.

Davis was a prominent man without experience in electoral politics when he sought the Democratic nomination for governor in 1917. He campaigned hard among the state's farmers. The party was divided on the issue of the prohibition of alcohol, and he endorsed local option to try to appeal to both sides without alienating either. Davis easily won a three-way race against two supporters of prohibition, Lieutenant Governor James Taylor Ellyson, who ran with the support of the party's leaders, and Attorney General John Garland Pollard. In spite of intense dislike of Davis by many members of the Democratic Party's entrenched organization who resented his swift rise to party leadership, in the November general election he easily defeated Thomas Jackson Muncy, a little-known Republican who ran with strong support from prohibitionists.

As governor of Virginia from 1 February 1918 to 1 February 1922, Davis presided over the state's participation in World War I during his first year in office and over the creation of a network of state highways during the second half of his administration. In 1919 violence erupted in southwestern Virginia between coal miners who were members of a union and miners who were not. Unlike many federal and state officials elsewhere who mobilized public opinion and the National Guard to break strikes or impose order through force, Davis personally visited the miners and negotiated a truce between the opposing groups. He was most proud of introducing the state's first executive budget, although the legislation creating it was a product of the General Assembly. Davis promoted businesslike management of the state, created a centralized purchasing system, terminated the leasing of convicts from the state penitentiary to private contractors, and created prison fabrication industries that produced furniture, clothing, shoes, and other items for the penitentiary and for state government offices.

Combative by nature and self-righteous, Davis was sympathetic to the progressivism of the 1910s and developed a deep animosity toward the Democratic Party organization, which he believed thwarted progress and excluded too many people from participation in politics. He attempted to build a rival organization through political appointments, but it did not last beyond his term. After leaving the governor's office early in 1922, Davis ran against party leader Claude Augustus Swanson in the Democratic primary for nomination to the seat in the United States Senate that Swanson had held for a dozen years. Davis's attempt to break up the organization failed, and he lost badly. In the reinvigoration of the party that year, Harry Flood Byrd (1887–1966) emerged as one of the most powerful young leaders. He was elected governor in 1925 and succeeded Swanson in the Senate in 1933. Davis and Byrd intensely disliked and distrusted each other. Davis denounced Byrd's style of political leadership and his opposition to the New Deal of the 1930s. Davis established the Virginia Bureau of Research, which early in the 1930s issued bulletins accusing state government agencies of financial mismanagement. He departed so far from the political orthodoxy of the party late in the decade that he had the Southern Planter begin campaigning for elimination of the poll tax as a prerequisite for voting because it kept many poor white men from voting for reformers and against the Byrd organization.

Davis and his wife led an active social life after he was governor. Cattle and turkeys he bred and raised won prestigious prizes at national livestock shows, and from 1928 to 1931 he served as president of the Virginia State Fair Association. Westmoreland Delaware Davis became ill at Morven Park on 30 August 1942 and died on 2 September in a Baltimore hospital. He was buried at Morven Park. His widow established the Westmoreland Davis Memorial Foundation in 1955 to administer the estate as a museum and place of agricultural education.

Sources Consulted:

Biographies in Mitchell C. Harrison, comp., New York State's Prominent and Progressive Men: An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography (1900), 2:91–92 (with Paris birthplace), Robert C. Glass and Carter Glass Jr., Virginia Democracy (1937), 1:315–318, National Cyclopędia of American Biography (1891–1984), 37:510–511 (with marriage date), and Jack Temple Kirby, Westmoreland Davis: Virginia Planter-Politician, 1859–1942 (1968); Carolyn Green, Morley: The Intimate Story of Virginia's Governor & Mrs. Westmoreland Davis, ed. John T. Phillips II (1998), an imagined autobiography of Davis's widow; matriculation record signed W. D. Davis, Virginia Military Institute Archives, Lexington, Va.; Westmoreland Davis Papers, (including mother's genealogical notes with Paris birthplace), Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.; Westmoreland Davis Papers, Accessions 27881 and 40224, and Westmoreland Davis Executive Papers (online finding aid), Record Group 3, all Library of Virginia; obituaries in Richmond News Leader, 2, 3 Sept. 1942, and Leesburg Loudoun Times-Mirror, New York Times, Richmond Times-Dispatch, and Washington Post, all 3 Sept. 1942; memorial in Southern Planter 103 (Oct. 1942): 8.

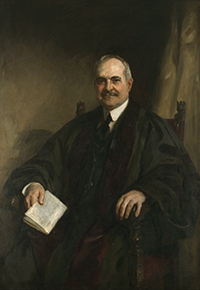

Image courtesy of the Library of Virginia, State Art Collection.

Written for the Dictionary of Virginia Biography by Brent Tarter.

How to cite this page:

Brent Tarter, "Westmoreland Delaware Davis (1859-1942)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (1998– ), published 2015 (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Davis_Westmoreland_Delaware, accessed [today's date]).

Return to the Dictionary of Virginia Biography Search page.