Lila Hardaway Meade Valentine (4 February 1865–14 July 1921), woman suffrage activist and social reformer, was born in Richmond, Virginia, and was the daughter of Richard Hardaway Meade and Jane Catherine Fontaine Meade. The Meade family Bible and her baptismal certificate record her first name as Eliza, but by the time of her marriage and ever after she signed her name and was always known as Lila Meade. On 28 October 1886 she married Benjamin Batchelder Valentine in the city's Monumental Episcopal Church, of which they were both lifelong members.

The Valentines lived briefly with his parents in their large and elegant residence in downtown Richmond before moving into their own house and later in the 1910s into a mansion on fashionable Monument Avenue. Her husband's family was socially prominent, and he was a prosperous officer of a successful family business. He had wide-ranging interests in history, literature, and archaeology and also wrote on a variety of topics. Before her marriage Valentine had been unable to obtain a formal higher education, but she and her husband read widely and extensively. The Valentines had no children. Following a failed pregnancy about 1888 she suffered from recurrent bouts of serious health problems for the remainder of her life. Valentine's afflictions included migraine headaches, debilitating and prolonged gastrointestinal problems, and susceptibility to respiratory illnesses.

In part for business reasons, but also in hopes of improving her health, Valentine and her husband made extended multiple visits to England from the 1890s through the 1910s. When they were in England, and she was well enough, Valentine went to the theater, the opera, symphony concerts, and museums, as well as visiting the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Social Reformer

In improved health following her return from England in 1899 and perhaps inspired by English social settlement work, Valentine quickly became involved in several social welfare projects. She was a board member that year of the Consumers' League of the City of Richmond. Valentine and several members of the influential Woman's Club of Richmond took part in founding the Instructive Visiting Nurse Association to provide health care for the city's poorest residents. She was a member of its board and was elected president in February 1904, but had to resign later that year as a result of her poor health.

Valentine and other members of the Woman's Club became interested in sponsoring kindergartens in the city, and in 1900 she helped organize the Richmond Education Association. While she was president from 1901 until her resignation in November 1904, the association's kindergarten committee persuaded the city to appropriate money for that purpose. After Valentine inspected a high school and found it dilapidated and infested with rats, she rallied some of the city's leading society ladies to publicize the school's condition and convince the city to appropriate money to replace it. Like some other white Virginia women of the time who advocated educational reform, Valentine insisted that the association promote better education for both black and white children. In the spring of 1902 she attended the convention of the Southern Education Board in Georgia and was so impressed with its plans to improve education for African Americans that she arranged for the next annual convention to be held in Richmond. Valentine was also active in the Co-Operative Education Association of Virginia, which was founded in 1904 to coordinate campaigns for improving public education statewide.

Woman Suffrage Activist

The cause of woman suffrage engaged Valentine's interest more than any other one progressive project, especially after she had met and observed English suffragists. Like other people who supported woman suffrage, Valentine believed that women would be able to make further progress on social and educational reforms if they gained the franchise, but Valentine also believed that the right to vote was a valuable right of American citizenship that neither Virginia nor the United States should withhold from female citizens. Valentine described the suffrage movement as "a clarion call to the woman of today. It bids her stand up and think for herself…." As long as women were "deprived of the educative responsibilities of self government," she continued in a 1916 speech to the annual convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, women will "fall short of complete development, as a human being." When about twenty prominent Richmond women founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia in November 1909, they elected Valentine president. The league affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association and she attended its annual national conventions from 1910 to 1916, until poor health caused her to miss them in later years.

During the first years of the state campaign for woman suffrage, Valentine and other suffragists in the state focused on educating the public. They made suffrage speeches at county fairs, from courthouse steps on county court days, before church groups, woman's clubs, labor unions, and other organizations, and brought nationally known suffragists to Virginia to speak. At those events they circulated petitions urging members of the General Assembly to support an amendment to the state constitution to grant women the vote. They sought and received endorsements from the Virginia Graduate Nurses' Association (later Virginia Nurses' Association), the state's division of the Farmers' Educational and Cooperative Union of America, the Virginia Federation of Labor, and from some local chapters of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.

Valentine became an accomplished and persuasive public speaker. She was extremely well informed on social and economic issues that she believed woman suffrage would benefit, and she had the ability to engage the sympathies of her audiences. Valentine and the other speakers faced serious opposition where they spoke, including hostile people "hooting outside" when she spoke on one occasion and throwing threw pepper at her on another occasion. In the mid-1930s a Suffolk woman recalled, "The first guest speaker, we had, was Lila Meade Valentine, whose gracious, womanly & cultured manner & appearance, won many cold hearts, besides making the rest of us very proud of our convictions." Sometimes she and others spoke on street corners or standing in open-top automobiles. Valentine reported to the Equal Suffrage League's October 1913 state convention that during the past year she had made an average of two speeches a week.

In 1912 Valentine and other state officers of the Equal Suffrage League lobbied and spoke to committees of both houses of the assembly, but assembly members did not propose an amendment to the state constitution then or when it met in 1914 or 1916. Her annual reports to the league's state conventions and to the National American Woman Suffrage Association document the work she and the state league's leaders did. The large though incomplete surviving files of her correspondence with those leaders prove that in between periods of bad health Valentine devoted an immense amount of time and energy to speaking, lobbying, organizing, writing, dictating letters, and doing other work for the cause. She developed close personal relationships with many of the women, who were devoted to her. Valentine's cousin Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis, of Lynchburg, was president of that local chapter and vice president of the state league beginning in 1911. Their exchanges of letters are especially valuable in documenting the work Valentine did during the 1910s, as are Valentine's letters to Jessie Fremont Easton Townsend, of Norfolk, another league vice president.

Organizing the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia

During Valentine's trip to England in the spring of 1911 she attended the convention of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies in London. After her return she, novelist Mary Johnston, and Elizabeth Lewis began to organize local leagues around the state. Suffrage supporters in cities from Roanoke to Alexandria invited Valentine and Johnston to speak and help form leagues. In the autumn of 1912 they traveled to southwestern Virginia. In at least seventeen separate trips from her home and headquarters in Richmond in 1915, Valentine organized twenty-one leagues on the Eastern Shore, in southeastern Virginia, in the southern Piedmont, and in northern Virginia.

Early in September 1915 Valentine and her husband spent two weeks in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where under doctor's orders he recuperated from an attack of bronchitis. He rested, but she did not. She made suffrage speeches at the corner of Atlantic and North Carolina Avenues in Atlantic City, and she took the hour-long trolley ride down to Ocean City, New Jersey, to speak there. Valentine also campaigned for woman suffrage in West Virginia, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and in both North and South Carolina.

In spite of the lobbying Valentine and other state leaders did and in spite of the work of local leagues, most members of the Virginia General Assembly refused to endorse woman suffrage during the decade. Valentine was extremely critical of impatient suffragists who gave up on quiet, educational persuasion and began to demonstrate in the streets and demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States. She correctly predicted that Virginia's legislators, a mere half a century after the Civil War and Reconstruction, would never approve an amendment to empower the federal government to force change on the state. Valentine also worked hard to reassure white supremacists that the provisions of the Virginia Constitution of 1902 would make it practically impossible for African American women to register and vote in sufficient numbers to endanger the disfranchisement of most African Americans the state constitution had made possible. Privately she acknowledged that all women who met the qualifications in any state should have the right to vote, but she opposed public efforts of African American women to advance the cause because she knew that would antagonize powerful southern political leaders. After the National American Woman Suffrage Association endorsed a federal amendment, Valentine supported it wholeheartedly.

The Nineteenth Amendment

By the end of 1915 the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was probably the largest woman's organization in the state. It had 9,662 members organized in ninety-eight chapters in eighty-one counties. Valentine continued to direct the organization of local suffrage leagues until after the United States entered World War I in April 1917. She arranged for the league to pay the expenses of two organizers from the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Eudora Woolfolk Ramsay (later Richardson), and Mary Elizabeth Pidgeon, to help organize leagues across the state. Valentine reported to the national association early in 1919 that "our present membership is over 20,000." Later that year league officials boasted that it represented "175 centers of suffrage sentiment in the state" and by 1920 had obtained about 32,000 signatures in support of woman suffrage. No civilian organization of Virginians ever had so many members before that time.

Several times during the campaign for woman suffrage Valentine had to stop working because of her illness or the poor health of her husband, who was also a member of the Equal Suffrage League and heartily endorsed her tireless work for the cause. He suffered from heart disease and other afflictions off and on for several years. She traveled with him to recuperate in the warmer South early in 1917 and later that spring to Baltimore where he spent time in a hospital. In the spring of 1918 they returned to Baltimore where she had a serious operation and did not return to work in Richmond until the autumn. Valentine was struck down with a severe case of influenza in the spring of 1919. Each of her absences threw the bulk of the work of the Equal Suffrage League onto the small but talented office staff she had recruited and a core group of committed state leaders.

Valentine's husband died suddenly on 10 June 1919. She spent the remainder of the summer recovering from the shock but was back in the office dictating and writing letters in September. That autumn Valentine promoted the organization of citizenship conferences throughout the state, which began in 1920 under the auspices of the extension department of the University of Virginia to educate women on how to register and vote. She also directed the league's strategy for ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. When the General Assembly held a special session in August 1919, Valentine wanted to lay the groundwork for ratification at the assembly's next regular session, but the efforts of the Virginia branch of the National Woman's Party to force the issue led to a resolution in the House of Delegates condemning the amendment. At the session during the winter of 1920, the assembly refused to ratify the amendment, but the efforts of Valentine and the Equal Suffrage League paid off when they helped secure the passage of a law to allow women to register and vote in case the federal suffrage amendment was ratified before the November general election. Members of both houses also passed an amendment to the state constitution to grant women the vote, but when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in August 1920 the state amendment was no longer necessary and it was not submitted to the voters for ratification.

Valentine survived a prolonged and debilitating attack of influenza in the winter of 1920 and suffered from another severe illness in the summer. At that time her doctor refused to let her read newspapers or receive visitors. Even her sisters could enter the sickroom only once a day and for a few minutes at a time. The Nineteenth Amendment was ratified while she was confined at home. Under the law the league helped the General Assembly pass, Virginia women began registering to vote in September. Tradition records that Valentine was too unwell to leave home but that somebody persuaded a registrar to go to her home and register her there. Her name appears in the poll book for the city's Lee Ward. It must have been a very great disappointment to her that she was not well enough on 2 November 1920 to go out on the damp and threatening day to cast a ballot in the first election in which Virginia women participated.

Valentine resigned as president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia in a letter to the final meeting of its board on 9 September 1920. The following day her letter was presented at the founding meeting of the Virginia League of Women Voters. The founders honored her and her work for woman suffrage by electing her honorary state chairman.

Death and Legacy

Lila Hardaway Meade Valentine died early in the morning of 14 July 1921 in a Richmond hospital following abdominal surgery. She was buried beside the body of her husband in the city's Hollywood Cemetery. A week after Valentine died, national suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt wrote that Valentine's "was the type of character which has builded our Republic and ever carried forward the flag of progress…. Even from her sick bed she led on. Brave, beautiful intrepid soul! What a loss she is, only those of us know, who have heard her public speeches, shared her private counsel and realized through long association, the never surrender quality of her character. She will remain enshrined in the hearts and memories of thousands of American women, as one of our greatest and best. May Virginia Men and women honor her memory by faithfully marching forward in the direction she so fearlessly led!" On 20 October 1936, Nancy Astor, viscountess Astor, a Virginia native and the first woman to serve in the British House of Commons, presented to the state on behalf of the Lila Meade Valentine Memorial Association a marble bas-relief of Valentine by artist Harriet Frishmuth for installation in the chamber of the House of Delegates. It was the first and remains the only memorial to a woman inside the Capitol of Virginia. Valentine's name is inscribed on the Wall of Honor of the Virginia Women's Monument installed on Capitol Square in 2018.

Sources Consulted:

Biographies in Elizabeth Dabney Coleman, "Genteel Crusader," Virginia Cavalcade 4 (Autumn 1954): 29–32 (with several portraits), and Lloyd C. Taylor Jr., "Lila Meade Valentine: The FFV as Reformer," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (VMHB) 70 (1962): 471–487; feature series in Richmond Times-Dispatch, 4, 11, 20 Oct. 1936; birth (with alternative first name Eliza) and marriage dates in Meade family Bible Record, Accession 37997, Library of Virginia (LVA); letters and family records in Valentine Family Papers, The Valentine, Richmond, Va., and in Meade Family Papers and Lila Meade Valentine Papers (including christening record with alternative first name Eliza, and typescript transcription of Carrie Chapman Catt to Adèle Clark, 21 July 1921, sixth quotation), both Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Richmond; correspondence, reports, speeches, and other materials in Equal Suffrage League of Virginia (ESL) Records (including first quotation in typescript National Convention Speech, 7 Sept. 1916; second quotation on reverse of letter from Ida M. Thompson to Fannie M. Walcott, 17 Nov. 1936; third quotation in Crissie Gill Brockenbrough to Miss Thompson, 8 Dec. 1936), Accession 22002, LVA; letters, annual reports, and suffrage speeches in Adèle Goodman Clark Papers, James Branch Cabell Library, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond; some correspondence in National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) Records and in National Woman's Party Papers (1913–1920), both Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Annual Reports of the Richmond Education Association (1902–1905) include Valentine's annual reports; ESL annual reports in published NAWSA convention proceedings, 1910–1919, including fourth quotation in 1919 Handbook (p. 304); Woman Citizen, 13 Sept. 1919, fifth quotation; Grace Erickson, "Southern Initiative in Public Health Nursing: The Founding of the Nurses' Settlement and Instructive Visiting Nurse Association of Richmond, Virginia, 1900–1910," Journal of Nursing History 3 (1987): 17–29; Sara Hunter Graham, "Woman Suffrage in Virginia: The Equal Suffrage League and Pressure-Group Politics, 1909–1920," VMHB 101 (1993): 227–250; Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States (1993); Elna C. Green, Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question (1997), 151–177; obituary and editorial tribute in Richmond News Leader, 14 July 1921; obituary in Richmond Times-Dispatch, 14 July 1921; accounts of funeral in Richmond News Leader, 15 July 1921, and Richmond Times-Dispatch, 16 July 1921.

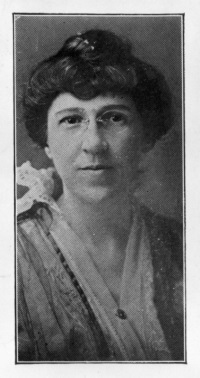

Image courtesy of Visual Studies Collection, Library of Virginia.

Written for the Dictionary of Virginia Biography by Brent Tarter.

How to cite this page:

Brent Tarter, "Lila Hardaway Meade Valentine (1865–1921)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (1998– ), published 2019 (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Valentine_Lila_Meade, accessed [today's date]).

Return to the Dictionary of Virginia Biography Search page.