Unfinished Business

On display from Feb. 26, 2020– May 28, 2021, Unfinished Business complemented our gallery exhibition, We Demand: Women's Suffrage in Virginia.

Extending the right to vote to women in 1920 was a milestone in American history. But much work remained to ensure that all citizens had a fair and equal voice in governing the country and shaping its policies. Unfinished Business, a series of panel displays, explored the fundamental question of citizenship through obstacles that limited suffrage to some Americans, including the Equal Rights Amendment (first introduced in 1923), extending citizenship to America’s Indigenous peoples, eliminating the poll tax and literacy tests, and the continuing advocacy for restoration of rights to felons.

Native Born but Not a Citizen

When women gained the ability to vote in 1920, most Native Americans were not considered citizens of the United States and could not vote. In 1884, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Elk v. Wilkins that the Fourteenth Amendment, which gives citizenship to anyone born in the United States, did not apply to indigenous Americans.

The U.S. Congress granted Native Americans citizenship with the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Nevertheless, barriers remained. State legislatures enacted laws to limit or disenfranchise indigenous American voters. Intimidation tactics included requiring that Indians terminate their relationship with their tribe, excluding members living on reservations, and imposing literacy tests.

In Virginia, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 complicated the status of indigenous Virginians by classifying all citizens as either white or “colored.” Walter A. Plecker, registrar for the Bureau of Vital Statistics, flatly denied that any true Native Americans lived in Virginia because they had intermarried with African Americans over the years. In Plecker’s mind, there were only white Virginians and black Virginians. The Racial Integrity Act was not overturned until the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Loving v. Virginia.

Virginia’s native peoples struggled for years to receive state and federal recognition. Today, the Commonwealth of Virginia recognizes eleven tribes: Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Mattaponi, Monacan Nation, Nansemond, Nottoway of Virginia, Pamunkey, Patawomeck, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi. Seven tribes have received federal recognition: Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Monacan, Nansemond, Pamunkey, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi.

African Americans, Suffrage, and the Right to Vote

Securing the right of African Americans to vote required federal amendments, federal legislation, and U.S. Supreme Court rulings. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, stated that voting could not be restricted “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Many white suffragists resented the fact that African American men were able to vote while women were not. The 1902 Virginia Constitution restricted black votes through tactics such as “white primaries,” grandfather clauses, restrictions based on criminal records, and poll taxes. Those restrictions remained after ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

- White primary: a party primary in a southern state open to white voters only

- Grandfather clause: a clause creating an exemption based on circumstances previously existing, such as a provision in several southern state constitutions designed to enfranchise poor white citizens and disenfranchise Black voters by waiving strict voting requirements for descendants of men voting before 1867

- Poll tax: a tax of a fixed amount per person levied on adults and often linked to the right to vote

The Twenty-fourth Amendment, ratified in 1964, eliminated poll taxes for federal elections. Not until 1966 did the U.S. Supreme Court rule, in Harper vs. Virginia Board of Elections, that any poll tax was unconstitutional. Virginians Annie E. Harper and Evelyn Thomas Butts were the primary litigants. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed literacy tests and other restrictions.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder nullified a part of the Voting Rights Act that required southern states to get federal approval before making changes to their voting laws. This has made it easier for states to introduce new regulations such as voter identification laws that have made voting more difficult for some citizens.

Old Enough to Vote

The last in a series of amendments expanding voting rights, the Twenty-sixth Amendment provided that “the right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age.” States ratified the amendment on July 1, 1971, in just 100 days, faster than any other amendment to the Constitution. Although not part of the thirty-eight states needed for ratification, Virginia subsequently ratified the amendment a week later.

“Old enough to fight, old enough to vote,” a slogan first used during World War II, became the rallying cry of student activists during the Vietnam War. To many, it seemed unfair that eighteen-year-olds were old enough to get married, work, pay taxes, and serve in the armed forces, yet they could not vote or have a voice in their government. Upon ratification, 11 million potential voters were added to the electorate. Half of these young people cast their ballot in the 1972 presidential election.

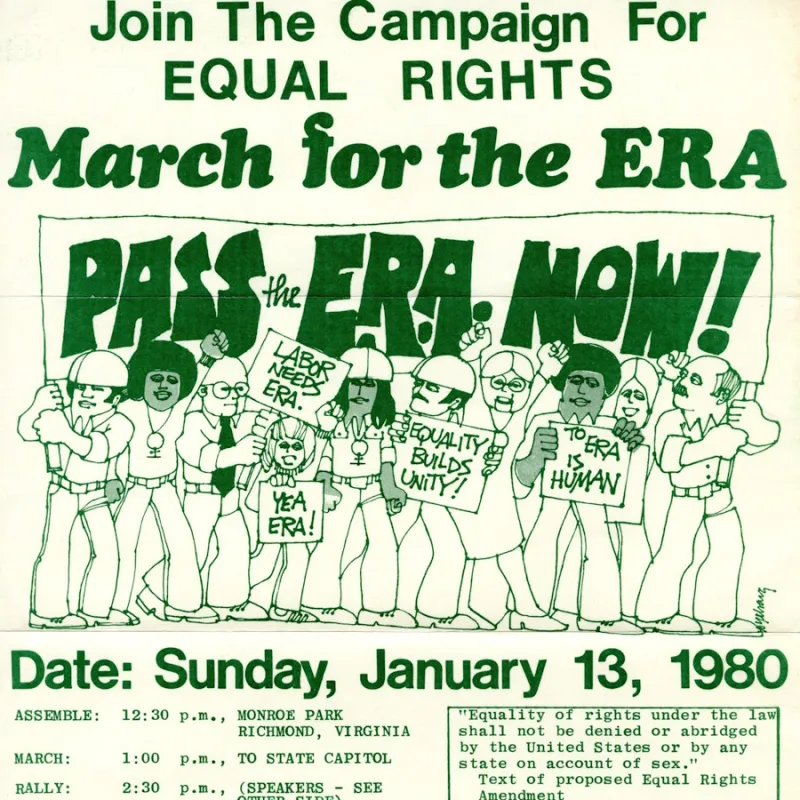

Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment was originally proposed in 1923 to guarantee that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex”.

In 1972, the U.S. Congress finally passed the ERA and sent the amendment to state legislatures for ratification. Groups like the League of Women Voters of Virginia and the National Organization for Women supported passage. The Virginia Equal Rights Amendment Ratification Council formed in 1974 to advocate ratification. The ERA faced stiff resistance, however. Opponents considered the ERA unnecessary and often used the same language that had been employed to argue against the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. The ERA, they claimed, threatened traditional values and laws that protected women and children. They argued that ratification of the ERA would allow women to be drafted, create unisex bathrooms, loosen abortion restrictions, and abolish gendered organizations.

Congress originally set a deadline of 1982 for thirty-eight state legislatures to ratify the amendment. By 1977, thirty-five states had approved the amendment; Virginia was not among them. Congress later extended the deadline indefinitely. Experts disagree on what it would mean if the amendment achieved the necessary state support. On January 28, 2020, the Virginia General Assembly became the required thirty-eighth state to ratify the ERA.

Criminal Justice and Restoration of Rights

Virginia is one of four states that does not automatically restore a convicted felon’s civil rights at the completion of incarceration and/or supervision. In Virginia, any person convicted of a felony loses the right to vote, serve on a jury, run for public office, and other civil rights. The governor has sole discretion to restore civil rights and only on a case-by-case basis.

Governor Bob McDonnell restored rights to a larger number of nonviolent felons (8,013) than any of his predecessors. In 2013, he unsuccessfully sought legislation to allow for automatic restoration of rights for nonviolent felons. On April 22, 2016, Governor Terry McAuliffe signed an executive order that restored voting rights to more than 200,000 convicted felons in Virginia. The Supreme Court of Virginia ruled that the order violated the Constitution of Virginia because the governor did not have the authority to grant blanket pardons and restoration of rights. In response, McAuliffe restored voting rights to almost 13,000 felons individually, using an autopen, a signature machine. By the end of his term, McAuliffe had restored voting rights to more felons than any other governor in U.S. history.

In 2017, the Virginia Senate passed a constitutional amendment (Joint Resolution 223) to restore rights automatically to those convicted of nonviolent felonies who have completed their sentences and paid all fines. The amendment died in the Virginia House of Delegates Committee on Privileges and Elections.

Campaigning for the Vote Continues

Virginians have continued fighting for equal access to the right to vote into the twenty-first century. Learn more about some of Virginia's changemakers in our online resources.

The UncommonWealth Blog

Learn more about America's unfinished business regarding voting rights in our series of exhibition-related blog posts.

Explore